“A piece of property abandoned, weeds grow up, a window is smashed.”

That line comes early in “Broken Windows,” one of the most widely quoted articles on policing. The theory offered up by those authors has been linked with changes in policing that ranged from zero tolerance of petty crimes, like graffiti and panhandling to significant interventions, such as New York City’s “stop and frisk.”

But as an article in the New Yorker asked as recently as two years ago, what if we had gotten the whole idea wrong. “What if vacant property had received the attention that, for thirty years, was instead showered on petty criminals?” Should we have then, and certainly now, focused our interest not on those small acts of disorder but on the environment where they thrive. Every day there are more and more headlines of increasing crime in our major cities. At the same time, we battle over funding or defunding the police - scientific study offers some insight and, I believe, a practical new direction.

Before jumping into the latest research, let us briefly consider the studies on policing involving the “Broken Windows” philosophy. First, and most important, what constitutes disorder and what policing procedures should be instituted is never made explicit. We see “broken window policing” that ranges from polite reminders to ticketing and fines to stop and frisk. The outcomes, too, are somewhat unclear, is a reduction in crime, a reduction in misdemeanors, or serious violent crime. As a result, supportive studies can be found on both sides of the funding/defunding argument. As George Kelling, one of the two authors of “Broken Windows,” writes in 2015

“…broken windows was never intended to be a high-arrest program. Although it has been practices as such in many cities, neither Wilson nor I ever conceived of it in those terms. Broken windows policing is a highly discretionary set of activities that seeks the least intrusive means of solving a problem – whether that problem is street prostitution, drug dealing in a park, graffiti, abandoned buildings or actions such as public drunkenness.” [emphasis added]

What if we change the built environment?

Prior studies looking at violent crime around abandoned buildings or vacant lots in Philadelphia looked at crime rates in those areas, comparing buildings and lots that were repaired and cleaned up to those that were not. In three months, there was a 39% reduction in gun violence associated with building improvement; a more extended nine-year study demonstrated a smaller 5% reduction in gun violence with cleaning up vacant lots. Researchers estimate that every dollar spent on remediation resulted in $5 to $26 in savings to taxpayers. Those early pilot studies set the stage for this current report, again from Philadelphia, on how improving the built environment impacts crime.

The current study

Philadelphia’s Basic Systems Repair Program (BSRP) provides low-income homeowners with grants to repair damage to their homes. With many of these homeowners living at or below poverty levels, home repair is not a priority. This condition can be found in numerous urban centers; New York, Newark, Detroit all come readily to mind. These grants of up to $20,000 require an application and involve a waiting period of roughly two-and-a-half years – applicants are motivated. The researchers had access to the applications, crime statistics from the Philadelphia police creating a single variable to categorize seven crime categories. [1] Their outcomes, broken down by blocks, covered the period 2006 to 2013.

6732 blocks of 19,869 blocks within the city received BSRP interventions. The homeowners were predominantly black, about 78%, or Latino, 12% with a mean annual income of about $12,000. Blocks without BSRP remediation had smaller Black populations, less unemployment, and higher annual incomes.

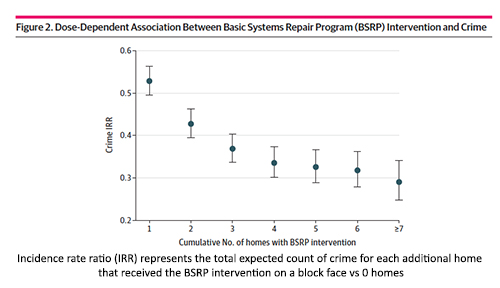

Home improvements were associated with 5.6 fewer crimes on these blocks over the seven years. That is a roughly 20% reduction each in assaults, robberies, and homicides. The researchers also describe a dose-dependent relationship, where more improved homes on a given block resulted in lower crime rates.

Home improvements were associated with 5.6 fewer crimes on these blocks over the seven years. That is a roughly 20% reduction each in assaults, robberies, and homicides. The researchers also describe a dose-dependent relationship, where more improved homes on a given block resulted in lower crime rates.

The effect was modest, but one can reasonably argue that it not only reduced crime but simultaneously improved the housing of the recipients. I would offer a simple proposal to those in New York City’s mayoral race – one that is anticipated to be all about law and order.

A modest proposal

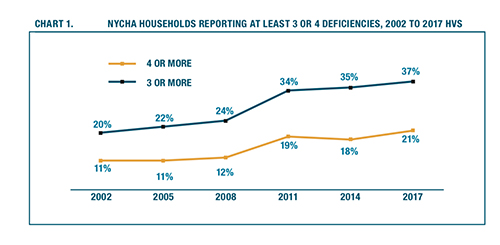

New York City’s Housing Authority (NYCHA) has 400,000 tenants, roughly 4% of the city's population, 20%of violent crime “occurs inside or within 100 feet of public housing developments.” Despite pie-crust promises, easily made and easily broken, involving several mayoral administrations and both political parties, the number of complaints involving significant deficiencies continues to escalate – this includes heating, leaks, mold, major repairs, and non-working elevators.

New York City’s Housing Authority (NYCHA) has 400,000 tenants, roughly 4% of the city's population, 20%of violent crime “occurs inside or within 100 feet of public housing developments.” Despite pie-crust promises, easily made and easily broken, involving several mayoral administrations and both political parties, the number of complaints involving significant deficiencies continues to escalate – this includes heating, leaks, mold, major repairs, and non-working elevators.

Why not a grand experiment. Let’s fix the NYCHA housing, use those $! billion in funds that have already been “defunded” from the police. And then we can watch the changes in crime. At the very worst, there will be little movement in crime but a significant improvement in housing. If you believe the science, then we should also see a crime reduction. Let’s given broken windows another try.

[1] “homicide, assault, burglary, theft, robbery, disorderly conduct, and public drunkenness”

Source: "Association Between Structural Housing Repairs for Low-Income Homeowners and Neighborhood Crime" JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17067"